Lena Mandell

Ms. Healy

AP Literature

5 February 2014

Shakespeare lived in a peculiar time for women. While they were expected to be frail, dimwitted, and hold little agency, Queen Elizabeth, a woman, had just finished her reign of England. Women at the time “had no vote, few legal rights, and an extremely limited chance of ever getting an education, much less a job. There was no room for the independent single woman—except, of course, in the throne room” (Papp and Kirkland). The inconsistency with which women were treated, some as possessions, others as royalty, is apparent in Shakespeare’s play King Lear which tells the tragic story of a king who gives away his land and authority to two of his three daughters. On one hand, Shakespeare seems to have an enlightened opinion of women: like Queen Elizabeth, Goneril and Regan are powerful, assertive rulers. On the other hand, these two are demonized, and docile Cordelia is depicted as the most virtuous. Cordelia, the heroine, is celebrated for her devotion to others. Ultimately, even though the play has women in power, it depicts them in a classical and oppressive manor.

Shakespeare characterized the ideal woman in terms of her relation to men. Cordelia, a symbol of love and femininity, is portrayed as such because she is loyal to men. To begin with, she separates herself from her sisters by holding a greater affection towards her father, not by her own merit or accomplishments. Cordelia claims her future husband will take with him “half her care and duty” (Shakespeare, 1.1.913), leaving the rest to her father and no obligations to herself or to the rest of society. Her obligations are confined to the private sphere. He also purports the oppressive notion that women should be entirely selfless, solely concerned with household matters. Rather than portraying an ideal women as someone with ambition, passion, or intelligence, Shakespeare represents one who only has a domestic purpose. This is consistent with a traditional portrait of woman; someone who is loving and caring without individual needs and desires: the property of her husband or father. The patriarchal belief is even further demonstrated when the King of France tells Lear that Cordelia was his “best object” (1.1.245). Referring to a woman as an object denies her personhood, and her individuality. It wrongfully makes her life meaningful only in her helpfulness to her father and husband. While it is acceptable to explore a woman’s responsibilities to her family, it is not when few other aspects of her personality are highlighted.

The traditional mindset is even clearer when one looks at Goneril and Regan. Unlike Cordelia, they are obsessed with power and their interests are mostly selfish. Throughout the play their are vilified because of it. The King later describes Regan as a “vulture” possessing “sharp toothed unkindness” (Shakespeare, 2.4.152). The sexism is not in King Lear’s accurate insults, but in the way the two women are written. The ambitious women have no kindness. The kind woman has no ambition. There is no middle ground. This would not be so problematic if Cordelia showed any autonomy. After all women can be cruel and unjust. But, because Cordelia’s goodness is found in her obedient, selfless affection, and the sisters’ wickedness is in their self interest, Shakespeare’s work implies that women should not ever seek to serve themselves or to hold power, but should be content allowing men to rule. He suggests that giving women power is dangerous.

Still, the forceful representation of women is admirable. In classic works, a strong, ruling woman is rare. He may show that a woman has the ability to rule, and the strength to take command, even if she is a villain but, because of the lack of a balanced, complex female character the play still entrenches sexist gender roles. This mixed portrayal of woman is consistent with the times. A woman could be a leader, but that was an exception. And that exception would be consistently compared to the norm, men. After Lear goes mad, he even says Goneril and Regan are not “men o’ their words” and laughs at the thought of “Goneril with a white beard”(4.6.115). This suggests that a dominant woman is more like a man than one of her own sex. Shakespeare, perhaps, was mirroring Elizabeth’s own sentiment about herself; describing herself as “a week and feeble woman” with the “heart and stomach of a king”, implicitly sating that being like a man is the only way to be qualified to command. Typical of his time, Shakespeare considers leadership to be a masculine trait and so handicaps a women’s ability to succeed in society.

The incongruous attitude regarding women’s roles in society during Elizabethan times is clear in Shakespeare’s King Lear. He holds women to be simultaneously objects and to be capable of ruling and helping lead a war. Goneril and Regan are powerful, but treacherous and unjust, and Cordelia is admirable, but an object. So, ultimately with close examination, King Lear’s verdict on the matter of women is clear, they belong in the house, not on the throne.

Papp, Joseph, and Elizabeth Kirkland. “The Status of Women in Shakespeare’s Time.” EXPLORING Shakespeare. Detroit: Gale, 2003. Student Resources in Context. Web. 22 Jan. 2014.

Shakespeare, William. “King Lear.” Folger Digital Texts. N.p., 1603.

Web. 22 Jan. 2014. <http://www.folgerdigitaltexts.org/#http://www.folgerdigitaltexts.org?chapter=5&play=Lr&loc=p>

Queen, Elizabeth. “Elizabeth’s Speech at Tilbury.” Elizabeth’s Speech at Tilbury. N.p., n.d. Web. 05 Feb. 2014. <http://tudorhistory.org/primary/tilbury.html>.

Julia Kruk

Ms. Healy

AP Literature

22 January 2014

The Faction of Justice in King Lear

William Shakespeare’s King Lear captures a very discomforting reality that can be considered ahead of its time. The tragic events that all but destroy the English court illuminate a separation between justice in the eyes of the characters and justice in the context of nature’s power. The play is host to a divide between the experiences of men and the will of divine beings, which stands apart from the customs of England’s religion-tinted society of the Elizabethan Era. The victims in King Lear each had their own expectation as to what justice is like; each questioned whether it exists in human society at all. And although there were no definitive answers to such queries, the events of the play showed that justice was in fact served, however is was entirely different from justice in the eyes of men.

Within the human context of the play, justice was entirely subjective. Lear, Gloucester and Edgar, the three characters that had experienced the most cruelty, each had their own take on the nature of it. They were all victims that questioned the possibility of redemption. King Lear was abused by his daughter’s Goneril and Regan and was thrown out into a raging storm. He was driven mad by anger and grief, and was left to wander the outdoors. In his suffering and madness, Lear acknowledged the subjectivity of justice, saying: “See how yond justice rails upon yond simple thief. Hark in thine ear. Change places and, handy-dandy, which is the justice, which is the thief?” (4.6.166 -169). Lear believed that justice was a feigned element of human interactions that is a false hope for those who were wronged. He told Gloucester in the field:

“There thou

might’st behold the great image of authority: a

dog’s obeyed in office.

Thou rascal beadle, hold thy bloody hand!

Why dost thou lash that whore? Strip thy own back.

Thou hotly lusts to use her in that kind

For which thou whipp’st her. The usurer hangs the

cozener.

Through tattered clothes small vices do appear.

Robes and furred gowns hide all. Plate sin with

gold,

And the strong lance of justice hurtless breaks.

Arm it in rags, a pygmy’s straw does pierce it.

None does offend, none, I say, none; I’ll able ’em.

Take that of me, my friend, who have the power

To seal th’ accuser’s lips.” (4.6.172-187)

Gloucester also had reason to hope for retribution. He was betrayed by his own son, tortured for expressing his loyalty to Lear, and then thrown out of his own estate. Gloucester believed that the forces of nature and the will of the gods dictated human lives. He therefore acknowledged justice as something that was granted by the divine powers in the manner in which they chose. This is evident in the beginning of the play when he cites an oncoming eclipse as an indication of approaching turmoil. It is also clear when he thinks he is about to jump off the cliff, and he shouts:

“O you mighty gods!

This world I do renounce, and in your sights

Shake patiently my great affliction off.

If I could bear it longer, and not fall

To quarrel with your great opposeless wills,

My snuff and loathèd part of nature should

Burn itself out.” (4.6.44-50)

Edgar had also suffered. He was forced into extreme poverty by his step brother Edmund, and ultimately witnessed his father’s death. He believed that people would always get what is coming to them – that the guilty would be punished eventually. After he had slain Edmund, Edgar proclaimed “the gods are just” (5.3.168), expressing his satisfaction with the punishment he bestowed upon his half-brother. However not all the characters felt as content as Edgar with the way things played out. Characters like Lear, Gloucester and even Cordelia, may have felt that there was no justice for the cruelties they suffered. At the end of the play justice remained subject to the individual. Its nature and presence in society was debated, yet no conclusion was explicitly formed.

Justice in William Shakespeare’s King Lear seemed almost impossible because it was subjective. Each person had different expectations, and hence, they often did not find what they were expecting. However, this does not mean that justice did not exist within the greater world of the play. In fact, what the characters failed to notice was that justice was served. Every individual who committed a crime had died by the end: Goneril and Regan, who had abused their father; Cornwall and Oswald, who conspired with Lear’s daughters; Edmund, who betrayed his father and brother; Gloucester, who initially stood by as Lear was kicked out into the storm; Lear, whose greatest crime was that he had fallen from his natural state as king; and even the man who hung Cordelia. The only people who remained alive were Albany, Edgar and Kent, all of whom remained noble and loyal throughout the play. This was nature’s form of justice, which was a way of rebalancing the world in William Shakespeare’s King Lear. As Edmund had pointed out as he lay dying, “the wheel has come full circle,” (5.3.208). He was restored to his base state, and all the wrong he had done he was paying for with his life. Justice in the play was completely separate from the perspectives and expectations of the characters; it did not function according to degrees of guilt or any social customs. The justice that nature served was invariant: all those that had committed some act of treachery had paid with their life, quick and simple. There is only one apparent exception to this trend: the death of Cordelia. She was honest, loving, and even after being exiled and disowned by Lear, loyal. She committed no crimes and yet she died. This is because her death meant to prove an important point: although nature is not without a sense of justice, that does not mean that the virtuous cannot be victims of an unfortunate series of events.

King Lear by William Shakespeare proposed a very realistic take on justice in human society. The play demonstrated that it does not obey the social practices and human expectations. The justice that nature bestows is much different from the practices of court systems, and the divine powers rarely (if ever) work parallel to the will and hopes of men.

Works Cited

Shakespeare, William. King Lear. New York, NY: Folger Shakespeare Library, 1993. Print.

Hockey, Dorothy C. “The Trial Pattern in King Lear.” Shakespeare Quarterly 10.3 (1959): 389-95. JSTOR. Web. 20 Jan. 2014.

Carroll, Joseph. An Evolutionary Approach to King Lear. Rep. N.p.: Academia.edu, 2014. Print.

Ariadne Vasquez

Ms. Healy

English 7-period 2

1/22/14

Lear’s Madness

In King Lear, by William Shakespeare, madness is a prominent factor throughout the play. At first glance, madness is simply seen to engender tragedy within the plot. However, when one analyzes the madness of King Lear, one sees that there’s more dimension to this element that touches upon human nature. As Marvin Rosenberg states, “Shakespeare’s source of artistic data is human behavior,” (17) and Shakespeare does exactly that with Lear’s insecurities and future insanity to help reveal the absurdity of human greed. In the world we live in, people have created the idea of status that is awarded with rank, love and wealth. Those that are highest in status such as Lear are deemed powerful, but the painful truth is that they are not. When Lear has his proposed power, he is an old man, respected by all, but once he gives it away, the title of former king has no value and he’s only an old man. King Lear’s madness is the result of seeing reality clearly and also a haven to cope with the saddening truth that the most powerful monarch is equal as the poorest beggar with the only difference being self-proclaimed power.

Lear’s journey toward enlightenment begins with his irrational behavior at the start of the play from his insecurities of being an aged monarch. He feels unfit to continue his rule and decides to divide his kingdom in three to his daughters, but only after hearing an exaggerated declaration of love. The significance of Lear’s foolish approach to divide his power is that it emphasizes his need to reassure himself as a well-loved, powerful man still. This is also evident when he wants to keep his company of knights to remind him that he still has status. Lear wants the same respect he had when he was king, but once he is denied to keep his knights he realizes that without power he’s “helpless against the ravages of greed” (Mowat and Werstine xiii) from his own daughters. This revelation is the catalyst of Lear’s insanity and drives him out to the storm and to his discovery of the reality behind social status.

As Lear dwells in his madness during the storm, he becomes aware of the poverty and suffering that occurs in Britain and most importantly the injustices within social class systems. Although, Lear is clearly insane as he dons a crown of weeds and flowers on his head while he approaches Edgar and eyeless Gloucester, he has enough sense to lecture Gloucester on how the world works. He describes how every man is a sinner, but only the poor are victimized while the crimes of the rich go unnoticed, “Through tattered clothing (small) vices do appear. / Robes and furred gowns hide all.”(Shakespeare 4.6.180-81). Lear reveals that justice is tainted by our cruel system of social classes. We are all guilty of crimes, but only those with no power are persecuted.

Lear’s madness has also served as a method to cope with his grief. For instance, in the midst of the storm, Lear is oblivious to the dangers of the severe weather on his health. He instead scowls at nature and even rips his clothing off. Furthermore, Gloucester envies Lear’s insanity and wishes that he was mad as well to be free of sorrow, “Better I were distract./So should my thoughts be severed from my briefs,” (4.6.310-11). When Cordelia dies, Lear’s haven of delirium deteriorates and he slips in and out of sanity as he holds her lifeless body. “I might have saved her. Now she’s gone forever.” (5.3.326) are the cries of Lear in his agonizing state. The guilt of Cordelia’s death is the final strike to shatter the king’s soul. His madness can no longer suppress his pain and he finally reaches his end.

Lear’s insecurities are common in any person, “He is a troubled Everyman in the robes of a king,” (Rosenberg 18). However, he comes to the understanding that greed and power-hunger do not matter because everyone is the same with status only being a tool used by people to differentiate themselves. “Why should a dog, a horse, a rat have a life./ And thou no breath at all?” (Shakespeare 5.3. 3690-70) is important to highlight the idea that even the purest person such as Cordelia will reach the same fate as her wicked sisters—death. Hence, greed is a folly of human beings. Lear comes to this acceptance, but is driven mad.

Lara Brennan

Period 2

Ms Healy

AP Language and Literature

Edmund’s Soliloquy: Act 1 Scene 2

William Shakespeare’s King Lear addresses a wide array of social and political issues, but one of the most prominent is that of a rigid and unjust social hierarchy. Shakespeare uses a secondary plotline featuring Gloucester and his two sons; Edgar, and the illegitimate Edmund to emphasize this focus. In the play, Edmund is considered far inferior to his elder brother because he was born out of wedlock, and the way in which he is perceived by society prompts him to act with increasing dishonesty, vileness, and cruelty. In the beginning of Act 1 Scene 2 Edmund delivers a soliloquy in which he ponders his undesirable social status. Over the course of this speech, Edmund convinces himself to reject the cards fate has dealt him and to pursue any means necessary to attain the type of life to which he believes he is entitled. It is quite illuminating to examine the means through which Shakespeare carries out this character development. The evolution of Edmund’s emotional state is not only truthful on a human level, but also raises valid points challenging an unyielding Elizabethan social order.

Edmund begins by declaring “Thou, Nature, art my goddess; to thy law my services are bound” (Shakespeare 1.2.1) With these words Edmund audaciously confronts the arbitrary manner in which society constructs hierarchies. Edmund calls attention to the fact that these echelons stem from the imaginations of mankind, and ultimately are no real indication of one’s worth. Edmund believes that “the idea of “Nature” signifies a world without legitimacy. One is entitled to whatever one can gain by one’s wits. “ (Johnston) Edmund is deeply resentful of these unnatural forces, calling them “the plague of custom” (Shakespeare 1.2.3) which prevent him from being treated with fairness or respect. He is overwhelmed by a deep sense of indigence, proclaiming “my dimensions are as well compact, my mind as generous, and my shape as true as honest madam’s issue” (Shakespeare 1.2.8-10) This logic not only resonates with the minds of an audience, but serves as a mechanism for the advancement of the plot. As Edmund speaks, he is becoming more and more assured that he is correct in his planned course of action.

Shakespeare continues the development of both Edmund’s formulating plan and a simultaneous call for reason through the implementation of literary devices such as consonance and repetition. As Edmund wonders aloud why society feels the need to reduce people to labels, he asks “Why brand they us with “base,” with “baseness,” “bastardy,” “base,” “base”—“ (Shakespeare 1.2.10-12) The repetition of a strong, harsh “b-“ sound both commands the attention of listeners and allows Edmund to feel the immense weight this label holds. Each time Edmund repeats these phrases he is struck by their connotations. As the soliloquy progresses Edmund continues to focus on these labels. During the latter half of the monologue, whenever he refers to his brother he calls him “legitimate Edgar” (1.2.18) while referring to himself as “bastard Edmund” (1.2.19) or “Edmund the base” (1.2.22). It is reasonable to assume that Edmund is using these labels sarcastically as he has made it clear that he regards them as arbitrary. It is interesting to consider the fact that he outwardly denies caring about, and even mocks the social order, but is also desperate to attain his brother’s impending wealth and status. The distinction is that Edmund must do so by “creating for himself out of the materials at hand his own life to suit his individualistic desires.” (Johnston). Unlike his elder brother, Edmund has nothing handed to him.

The bitterness exhibited in the contemptuous way in which he discusses “legitimacy” is seen at many points throughout the soliloquy. He is not content with simply affirming his own worth, but also speaks scornfully against those who were born under traditional, “legitimate” circumstances which he describes as “a dull, stale, tired bed, go to th’ creating a whole tribe of fops got ‘tween asleep and wake?” (Shakespeare 1.2.15-17) Passages such as this one suggest that Edmund “relishes the notion of being a bastard because that is the most obvious manifestation of his commitment to denying traditions.” (Johnston) His disdain for the established system is such that defying it will not only satisfy his practical ambitions but will also leave him feeling personally vindicated. This ever-mounting bitterness helps fuel the fire behind Edmund’s determination.

The function of Edmund’s famous soliloquy is primarily to advance the plot of King Lear. It is an artistic device that allows the audience to witness Edmund’s thought process as he comes to the decision to act against the established system. It is also, however, a method through which Shakespeare can communicate directly with the audience. Although Edmund’s methods are unquestionably corrupt, his reasoning is quite logical to a listener. As the play progresses, the audience witnesses extreme lengths to which Edmund is driven and is forced to consider the hierarchies existing in their own societies and the dangers they might one day present.

Works Cited

Johnston, Ian. “Lecture on King Lear.” Lecture on King Lear. Vancouver Island University, 11 Nov. 1999. Web. 17 Jan. 2014.

Shakespeare, William. “Act 1 Scene 2.” King Lear. New York: Chelsea House, 1992. N. pag. Print.

Individual Projects:

Lena Mandell

Ms. Healy

AP Literature

5 February 2014

Lunatics

Once there was a king named Lear

What others said he wouldn’t hear

Betrayed his beloved daughter, dear

The other girls’ words sharp as spears,

They had him wander far and near

But who is it then left, standing here?

This deranged man can’t be him!

For this one acts solely on whim

Finding that which is not there

Hidden in the frigid air

It was all too much to bear:

Sizzled, white, matted hair

Buried in a hemlock crown;

A smile trapped inside a frown;

His tattered, shredded, dull red cape,

A souvenir from days escaped

He wore it all, yet, like a king

Oh what madness loss does bring!

Commentary on Creative Piece

In my poem, I tried to play with several motifs from Shakespeare’s King Lear, like the senses, family, loss, and madness. The first lines of my poem refer to Lear’s refusal to listen to Cordelia when she tell him she does love him as she should, or to Kent who counsel’s him against giving away all his land and excluding Cordelia. Like Gloucester, who is blind to his son Edmund’s tricks, Lear is also deaf to the truth. He will not recognize the obvious hyperbolic flattery in Regan and Goneril’s praise. Although, Gloucester is later blinded, Lear keeps his hearing. I also tried to briefly contrast Cordelia’s sweetness with her sisters’ cruelty by talking about how Lear betrayal of Cordelia right before the line about the sisters’ betrayal of Lear.

I wanted to also tried to explore loss’s effects on Lear by describing his tatterted state. I imagined a person finding him and struggling to recognize him. They ask themselves what is left of the old king. I thought the link between mad Lear and sane Lear was his royalty. Lear still discusses his authority even when insane, clinging onto it throughout his decline. I tried to portray this through the hemlock crown mentioned in the text and through inventing a cape that he would wear anyway.

Ariadne Vasquez

Ms. Healy

AP Literature

5 February 2014

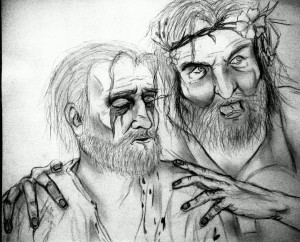

The king grasps the shoulders of his old, loyal friend and continues,

Look with thine ears. See how

yond justice rails upon yond simple thief. Hark in

thine ear. Change places and handy-dandy, which

is the justice, which is the thief? (166-169)

The blood soaked face Gloucester silently listens to Lear’s discourse of the justice system being a mere folly. It is what Edgar refers to as “Reason within madness!” (Act 4 Scene 6, 193). In this short moment of the play, Lear slips into sanity and elaborates on the fact that we all sin and are guilty of a crime, but only those deemed inferior by society such as a thief or even the poor are the only ones punished.

Lara Brennan

Ms. Healy

AP Literature

5 February 2014

Lara Brennan’s Creative Commentary on Act 3.2

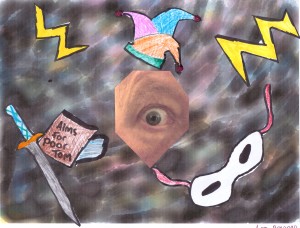

My collage focused on an interpretation of what occurs inside of Lear’s mind during the storm. The backdrop is, on one level, an abstract rendering of the literal storm, but is also meant to convey the confusion and uncertainty that plagues Shakespeare’s Lear. At this point in the play, everything Lear thought he could take for granted; his daughters’ love, his sense of control and security, the knowledge of who he could truly trust, had all fallen apart. I focused primarily on the the parallel presented by the way in which Lear’s personal world collapses as the traditional social order of his world and the people who inhabit it (Gloucester, Edgar, Edmund, the fool) does the same. The eye of an old man, his brow furrowed with fear and desperation, is the centerpiece of the collage. All around him objects representative of traditional societal roles are blown about by gales of wind, and worn down by a torrential downpour. The fool’s hat floats precariously closely to Lear’s own head, and the sword of a noble Edgar mingles with the tin of the mad beggar he appears to be. I hoped to call attention to the ephemeral nature of each of these roles, and the instantaneous way in which one’s position in the world can change. It is only at the height of the storm Lear can see this important truth. (Thus his eye, the lens through which he perceives, is placed at the center.) The focus on the eye also draws a parallel between Lear’s ability to perceive the truth only once in the storm, and Gloucester’s blindness to reality that does not cease until he blinded literally.

Julia Kruk

Ms. Healy

AP Literature

“Darkness and devils,

dogs and fiends,

bestow no greater misery

than truth does upon men who crept through their days utterly blind.

When nature flaunts its upper hand

and shatters all personas upheld by men,

there stands bare a cowardly ignorance,

dotage without the grace of wisdom

all but a shadow of a man who once stood his rightful place.

Hear nature, hear dear goddess,

here is a man as enraged, as versatile,

as the shifting winds of the menacing storm.

Here is a man who traded a crown of gold for one woven of rank fumiter and furrow-weeds.

And so with bustling laughter, nature pulls the strings

and as the world is wound by its will, the gods through their incense.

By its hand,

love cools, friendship’s fall off, brothers divide

in countries, discord

in palaces, treason

Machinations, hollowness, treachery

and madmen see reason.

nature can reason it thus and thus, yet nature finds

itself scourged by the sequent effects. Love cools,

friendship falls off, brothers divide; in cities, mutinies;

in countries, discord; in palaces, treason; and

the bond cracked ’twixt son and father.This villain

of mine comes under the prediction: there’s son

against father. The King falls from bias of nature:

there’s father against child. We have seen the best of

our time. Machinations, hollowness, treachery, and

all ruinous disorders follow us disquietly to our

graves. —Find out this villain, Edmund. It shall

lose thee nothing. Do it carefully.—And the noble

and true-hearted Kent banished! His offense, honesty!

’Tis strange.” (1.2.109-124) – Gloucester

As mad as the vexed sea, singing aloud,

Crowned with rank fumiter and furrow-weeds,” (4.5.1-3) -Cordelia

The wheel is come full circle; I am here” (5.3.507) -Edmund